Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s sandbox, from those who inspired him to those who were inspired in turn.

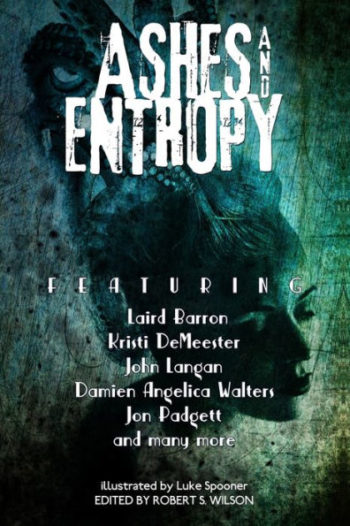

This week, we’re reading Wendy Nikel’s “Leaves of Dust,” first published in Robert S. Wilson’s 2018 Ashes and Entropy anthology. Spoilers ahead.

Beneath the interstate of the minature world within the broken branch itself, a hollow place catches Ysobel’s eye—a tangle of darkness, concealing a whisper of movement.

Ysobel, a woman no longer young, as genteel euphemism might describe her, has moved from the city to a house on a quiet cul-de-sac. There, hours away from everyone she knows, she hopes to be left alone while she mourns a failed relationship. Arranging furniture and unpacking boxes have left her aching, and she’s about to sit on the porch with a restorative cup of tea when the cherry tree in her yard cracks. The day is windless and cloudless, yet with “the ragged snap of tree-bone” and “magpies fleeing from its foliage in a burst of leaf and feather,” the cherry drops a major limb.

Abandoning her tea, Ysobel inspects the damage. The fallen bough covers half the overgrown grass she has no mower to cut, having never been responsible for her own lawn before. Deep inside the hollow branch, she spots something “not-quite-treelike… a tangle of darkness, concealing a whisper of movement.” The branch emits a sound like “the hum of a distant fan,” but before she can pin down its source, her (yet-unmet) neighbor calls over the fence: “Looks like you could use a chainsaw.”

The neighbor wears a bandana over wispy white hair, peers under bushy eyebrows with “small pinprick eyes.” Ysobel refuses the offer of help and retreats into the house. She hoped the cul-de-sac would afford her more privacy!

She leaves a message with a tree-cutting service. That night she dreams of the hollow branch. The darkness within calls to her in a voice “demanding and familiar.” Black tendrils of “glutinous sap” wrap around her arm and reel her in with slurps and gurgles that drown the traffic noise and envelope her in “silence so perfect, so absolute, she can barely breathe.” In the morning she finds her heels muddy, tree bark under her nails.

In daylight, Ysobel dismisses the dream. She’s tempted to leave the fallen limb undisturbed—let crabgrass and vines turn it into “her own personal forest,” blocking out the world.

The world insists on intruding. Her friend Bette, who almost became her sister-in-law, calls to check on Ysobel and offer help settling her into the new house. And, by the way, Bette spoke to him the other day. Ysobel cuts her off. She’s fine, she lies, needs no help, has to go and answer the door, must be the tree-cutter. Later, fallen asleep in front of the TV, she dreams the woody-cherry smell of the cracked branch has turned to “a heady mix of cologne and cigar smoke and the stench of bitter disappointment. In the hollow, luminous orbs bob “like champagne bubbles in a moonlit glass.” Ysobel sees her own pale and tired face on their surfaces, watches tiny cilia propel them forward as sticky tendrils part to reveal staring pupils. Next morning she brushes dirt from her teeth.

Someone wedges a greeting card in her screen-door—a Norman Rockwellesque print of a boy fishing graces the front; scrawled inside is “Welcome to the neighborhood,” a phone number, and an illegible signature. Ysobel tosses the card in the trash. She opens a moving box and finds the hundred-year-old book she once bought for him, a perfect gift. “Its brittle leaves are so frail that it seems like the lightest touch could dissolve them into swirls of dust.” Thought becomes deed, and bits of book come “fluttering down like dust-coated snowflakes.”

Determined to finish unpacking, Ysobel stays up all night. The TV blares the kind of ancient sitcoms her estranged mother loved. Though Ysobel means to switch channels, she sinks into her armchair, falls asleep, dreams of her yard transformed to a cathedral for the “broken-branch altar.” She approaches reverently, the stillness of its void calling her. Black tendrils curl around her like calligraphy. Eye-orbs slither out and bob around her, pupils dilated with “fervent expectations.” “Hurry,” the orbs whisper, “for it’s nearly dawn.” And looking eastward, Ysobel sees that there “the darkness is not so black nor the thickening haze so solid.”

The tendrils grip her tighter. The eye-orbs hiss disapproval. She gasps, yet isn’t what they offer just what she’s wanted? “No,” she says aloud, then shouts, struggling to free herself.

Something “rumbles to life” with a racket that drives off the tendrils and eyes. Does the “cathedral” crumble around her? Does she feel sun-warmth? Open your eyes, something commands. Ysobel does, to discover she’s in her armchair before a static-blaring TV. Outside the rumble persists, “loud and steady.”

Ysobel goes onto her stoop into morning light and watches the wispy-haired, bandana-wearing woman who’s chainsawing the fallen branch into “harmless plumes of dust.” The sawdust dissipates in an orange cloud against the red sunrise.

She returns to her kitchen, starts up the kettle, and sets out two mugs for tea.

What’s Cyclopean: The tree-thing has tendrils of “glutinous sap” that “curl like calligraphy.” They also “gurgle and slurp,” attraction-repulsion laid out in contrasting vocabulary.

The Degenerate Dutch: Ysobel worries about moving into “that sort of neighborhood—the sort where folks peer over fences and into others lives, where they say ‘Yoo-hoo’ and loan out garden tools.”

Mythos Making: As one of Ruthanna’s kids once said about a shoggoth, “it has a lot of eyes.”

Libronomicon: We never do find out the title of the hundred-year-old book that Ysobel bought her fiancé, or what made it such a perfect gift.

Madness Takes Its Toll: When you stare too long into the abyss, the abyss gets judgy.

Anne’s Commentary

On her author’s website, Wendy Nikel confides that she has a terrible habit of forgetting where she’s left her cup of tea. I hope she hasn’t ever forgotten her tea for the same reason Ysobel does, that is, the partial collapse of a strangely infested cherry tree. But I note that the photograph above her bio is of a suspiciously gnarly old tree that, yup, does appear to have shed at least one major branch.

Buy the Book

Flyaway

Short story writers and fans could profit by studying how subtly and pro

vocatively Nikel weaves clues about Ysobel’s past and present into her straightforward narrative. How old is Ysobel? Old enough to suffer the body aches of hefting furniture at an advanced age, but what exact age does that indicate? No exact age. Ysobel could be anywhere from thirtyish to seventyish, depending on the degree of self-deprecation with which she refers to her years. I figure she’s in the fortyish to fiftyish range since she’s not too old to attempt the furniture solo.

The point is, I get to figure this out for myself, as I get to figure out Ysobel’s backstory from gradually less cryptic hints. She doesn’t call one of the three listed tree-cutters because of (his?) first name. It’s a common name, yet there’s something painful in its particular familiarity to Ysobel. That’s a strong emotional reaction to coincidence. In her first dream, the branch-entity wraps a tendril not just around her arm or hand but around the “naked base of her fourth finger.” That’s the finger on which an engagement and/or wedding ring would be worn; that Ysobel senses it now as “naked” implies that she has worn a ring there recently, or has hoped to. Bette’s phone call partially solves the mystery—she was almost Ysobel’s sister-in-law, so Ysobel must have been engaged (or almost engaged) to her brother. More, the break-up was recent, since Bette tries to reassure Ysobel no one blames her, sometimes things don’t work out, we all still care for you, and, by the way, he called the other day—

At which point Ysobel backs out of the call. And what was her fiancé like? That picture we build from Ysobel’s perceptions of the branch-entity. Its voice is familiar (like the tree-cutter’s name) and demanding. Its smell changes from the expected wood-and-cherry to “a heady mix of cologne and cigar smoke and the stench of bitter disappointment,” all of which I’m assuming Ysobel associates with her fiancé. The glint and bob of the entity’s eyes are like “champagne bubbles in a moonlit glass,” which is practically image-shorthand for a proposal memory. Ultimately the branch dream-morphs into an altar in a cathedral, and Ysobel approaches it with reverence, like a bride processing to her waiting groom. Tendrils become calligraphy (rarely seen except on the envelopes of wedding invitations); the entity’s many eyes do double duty as those of both groom and congregation, “filled with fervent expectations.”

Yet wedding-bound Ysobel wonders if she shouldn’t be struggling, resisting, fighting a battle of wills against the groom-entity whose tendrils she begins to experience not as invitation but as slick and icy and stringent, whose eye-orbs start to hiss disapproval. Yet, yet, all she wants is to turn from darkness and thickening haze to the sun!

Talk about getting cold feet, and it sounds like for good reason.

“Leaves of Dust” is essentially the story of how Ysobel shrinks into isolation after her break-up with Bette’s brother. She’ll never trust anyone again; why don’t these new people KNOW she doesn’t WANT their attention and overtures of friendship? She needs to work on “her life, her diet, her health, her eternally-strained relationship with her mother.” Wait, that last one implies she needs a relationship to somebody. And if she really wanted a whole new existence, why did she drag along “a hodgepodge mess of things she never wanted but couldn’t bear to throw away.” Such as the expensive antique book that was to be a special, perfect gift to fiancé. That she tears the book into leaves of dust, she afterwards labels a “harsh and horrible deed” instead of a healthy impulse towards recovery, which proves she hasn’t recovered yet.

Recovery stalls until she again refutes fiancé by turning “I do” into “No!” in a second symbolic wedding ceremony. Here’s where the SFF component enters what could have been a strictly mainstream story. Fantastic elements do this often in contemporary fiction; I speculate it’s because fantasy is superlatively qualified to heighten the emotional impact and thematic complexity of a piece. Ysobel’s struggle with the sequelae of bad love could have been dramatized with realistic elements alone. Say her tree had a bough infested by whatever nasty beetle prefers cherries. She could have fed and watered and spot-pruned and dusted the tree until she dropped, or the branch dropped on her. Or she could have cut the sick bough off to save the tree, probably with the help of Bandana-Woman, which would represent Ysobel’s return to community.

Instead Nikel makes Bad Love a monster, a tendriled and many-eyed Lovecraftian beastie that sucks away at Ysobel’s energy. Why her? Maybe beastie can sense the psychic vulnerabilities of potential prey, and right now Ysobel’s lousy with vulnerability. Say that beastie dream-probes her memory for specifics. It can then use those to reconstruct the exact scenario that will lure her into a “marriage” consummated in her death or (worse) into some unspeakable union of alien and human, alien prevailing. What can save Ysobel?

First, she must struggle. Second, she must tell the monster NO. Third, she must yell for help. Fourth, when help shows up with a chainsaw, she must accept that help. Finally, she must accept the helper, and what better way than with a cup of tea?

The usual question applies: Is the branch-monster real, or is it in Ysobel’s head, flesh-and-ichor or metaphor? I don’t know that there’s a definitive answer in the text, or that there’s meant to be one.

Me, I always go for the flesh-and-ichor. Very tasty, especially with a side of icy tendrils.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

I’m liking the flavor of weird that seems to characterize Ashes and Entropy. “Leaves of Dust” is a much quieter story than Geist’s “Red Stars | White Snow | Black Metal,” but they have commonalities. The line between mundane and cosmic weirdness blurs. Female narrators pull away from terrible men (a boss, an ex-fiancé) and into the strange, the dangerous, the abyssal. And the abyss reflects what, in a fit of romanticism, I’m going to call the abyss of the heart. For Geist’s Kelsey, that abyss is righteous anger metastasizing into nihilism. For Nikel’s Ysobel, it’s the rejection of one relationship-gone-wrong metastasizing into a despairing rejection of all relationships.

Kelsey doesn’t even think of pulling back. Ysobel, who might seem at first glance weaker, is (literally) a different story. The thing in the tree—or the dream of the thing in the tree—puts slimy, eye-ful not-quite-flesh on the abstract temptations of perfect isolation. And even with the slime and the gurgling, she finds it tempting, with its tar-stalks (like tar babies?). Perfect silence, and a place where she’ll never need anyone again.

And trying to figure out why that’s tempting, the boundaries blur again, this time between the leaves of the tree and the leaves of a book. Like the fiancé, the book intended as a gift for him is defined almost entirely by negative space. We know it’s an antique, and we know it was a “perfect gift.” But knowing nothing about him except for his effect on Ysobel, we can’t determine whether perfection comes in the form of a numismatic textbook or a 2nd edition Necronomicon. Boxes are described as “tomes devoid of words,” but the actual tome is similarly devoid. The leaves of the tree tell us more than the leaves of dusty paper.

Except that they don’t, really. We have no more real idea what’s in the tree than what’s in the book. It might be a fate worse than death, but perhaps not a fate worse than the marriage she narrowly avoided. At least the abyss is honest about its nature.

And yet—defying decades of assurances that the vast uncaring universe is uncaring, Ysobel worries that the void is maybe judging her. That it disapproves of her initial surrender, her moment of complacency in the face of whatever it intends for her. Its eyes are filled with “fervent expectations,” as terrible as the expectations of neighbors who peer over fences and loan out power tools. That just might tell you more than you wanted to know about her ex. Maybe the void will come for him next?

Ysobel, on the other hand, has broken through her complacency, just as she must have to make her move in the first place. The tree-thing has done her a slime-eyed favor, forcing her to choose between running away from everything into the uncaring void/impersonal suburbs, and running to new places and new relationships.

Hopefully the chainsaw-wielding neighbor is more friendly than nosy. It sounds like Ysobel has had enough judgmental eyes, human and otherwise, to last a lifetime.

Next week, an interesting-looking prequel by Robert Price to “Haunter in the Dark” called, of course, “The Shining Trapezohedron.” You can find it in the Third Cthulhu Mythos Megapack.

Ruthanna Emrys is the author of the Innsmouth Legacy series, including Winter Tide and Deep Roots. Her short story collection, Imperfect Commentaries, is now available from Lethe Press. You can find some of her fiction, neo-Lovecraftian and otherwise, on Tor.com, most recently “The Word of Flesh and Soul.” Ruthanna is online on Twitter and Patreon, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.